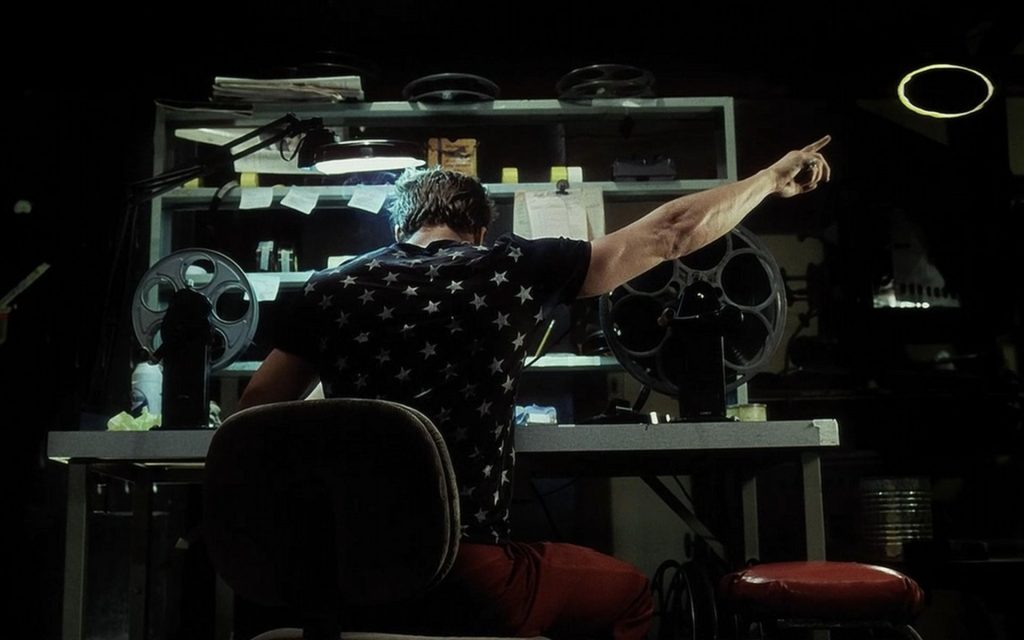

Fairbanks — Cigarettes and celluloid. Thick clouds of smoke. A dim light and the snip-snip-snip of film being cut. In the middle of it all, a shadowy figure hunched over a film reel cutting away. Usually some mix of these elements are what make up the typical — if rare — Hollywood portrayal of a film editor at work

In any movie about making a movie the mysterious editor works alone, cutting away at strips of film stock.

Today things are a bit different. Missing are the large rolling bins used to transport and categorize film clippings and gone are the scissors and the cutting table. Editing is largely done digitally. Hours of raw footage are whittled down to minutes of completed video. It’s editors who decide what stays and what gets left on the ‘cutting room floor’ — a term still standard in the industry despite the disappearance of physical film. But unlike directors and actors, their methods are not common knowledge.

Daniel Walker’s basement office with its bright red back wall is neither dim nor full of smoke. There’s no dirty ash tray in sight, just a couple computer monitors on a desk and some camera gear scattered around. “I don’t think I’ve ever been the one being interviewed before’ said Walker, who works for several local production companies. Between that work and his personal projects, there’s plenty of editing to keep him busy. Editing interviews, he knows how he’s going to represent people — straightforward, cutting filler expressions like “uhh’ and “um’, presenting the interviewee’s comments as accurately as possible.

But unlike with interviews, ethical representation isn’t the guiding light when it comes to narrative fiction films. It’s acceptable — expected, even — that fiction editors will cut and splice an actor’s performance however they see fit to really make a scene shine, Mika McCrary said, even if that means taking things out of context and reordering a sequence of events. She’s an editor for the University of Alaska Fairbanks eCampus department. Both her and Walker are accustomed to working on both sides of the divide between reality and fiction. In one short film, McCrary edited, an actor’s lines weren’t very consistent making it difficult to cut around them. If an actor is slouching forward in one take but leaning back in another, viewers might notice the inconsistency between them. But continuity doesn’t ultimately drive the entire process. McCrary sacrificed smoother cuts in favor of highlighting the best parts of that actor’s performance. And Walker’s mentality?

“Samuel L Jackson is horrible at continuity,’ he pointed out, “but the emotion is there.’

While working on a short film with actor and film student Kelsey Nore, Walker said they even did reshoots to get a better performance. When they looked at it together in an early edit, it just needed to be better.

Actors like having input on the edit. This isn’t always a good idea, said Nore, who worries that his suggestions will be biased toward his own performance. That’s too many voices in the editor’s sphere — voices which, he said, “may not even be qualified.’ An actor or director might love one take, even though it’s not the best.

It’s the job of the editor, he said, to counter and say “that’s not our best take,’ applying his skills and understanding of the director’s vision to carry it out.

Jared Olin, a biology student-turned-actor, doesn’t even like to view his work during the editing process. When an editor brought him into the editing room for input, Olin avoided looking at the screen. He puts his trust in the editor to do their thing. Acting in Discovery’s “Ice Cold Killers’ last year, his 10-second part expanded to a couple minutes during editing; “they made me look really good,’ as the actor put it.

But that doesn’t always happen. Olin recalled another experience in which the editor chose to cut to a shot of him in an intense climactic scene. He cringed at the finished film.

Nore has had similar experiences. On one shoot, the director called for numerous takes of his performance during a scene with a major shift of emotion. It was difficult to get the character right over and over again. Even he doesn’t buy his own performance in the finished film.

Both actors wonder why a better take didn’t make the final cut.

McCrary feels this responsibility to actors every time she edits. “I’m pretty aware of it,’ she said, followed by a chuckle. “I try to put the best performances out there’.